BBC Cult - Printer

Friendly Version

The Sands of Time - Instalment

Four

Page 1

Chapter Five

Atkins was not at all sure how to approach Lord Kenilworth. He spent most of the time in the TARDIS on its journey back to 1896 pondering the problem. The Doctor had made it clear what it was he was proposing and that he thought Atkins should perform the introductions. But Atkins felt that it might be seen as a little presumptuous for him to suggest to his master where he should direct his latest expedition.

So as they entered the lobby of the Mena House Oberoi hotel in Giza, Atkins decided his best recourse was to repair to the bar to get his spirits up. Or rather, down.

‘What a splendid idea,’ the Doctor said, pointing across the room. ‘How did you know he’d be here?’

Atkins said nothing. Now that he could see Lord Kenilworth, maps and papers spread out on the table in front of him, Atkins realised that the bar was indeed the most likely place for him to be.

‘Well, go on then,’ the Doctor hissed in Atkins’ ear. He elbowed him into the room, and gestured for Tegan to stay near the doorway. ‘Let us handle this,’ he said quietly to her. Tegan’s grunt of annoyance melded with Kenilworth’s snort of surprise as Atkins crossed the room towards him.

Atkins kept his expression as blank as he could as he crossed the room. Kenilworth wiped a handkerchief across his face and stood up, as if not quite able to believe what he was seeing. ‘Good God, Atkins - what the deuce?’ he gruffed as Atkins came within range.

‘I’m sorry, sir. I realize this is somewhat unexpected.’ Atkins bowed his head so as not to meet his employer’s eye. ‘But a matter has arisen.’

‘Unexpected? I should say so.’ Kenilworth waved him to a chair by the table.

Page 2

Atkins sat, his legs suddenly feeling less secure as he took his weight off them.

‘So what is this matter that brings you all the way from London?’ Kenilworth leaned across the maps and documents at Atkins. ‘What is it that causes you to neglect your duties - and my household, I should add - and come to Cairo in person rather than send a telegram?’

Atkins coughed politely. ‘We are actually in Giza, sir,’ he said, wondering how best to explain the situation.

‘I know where I am, thank you.’ Kenilworth sat back in his chair. He picked up his whisky tumbler, and made to take a sip. Then he changed his mind and held it up to the light instead. ‘And I rather think I may be permitted to stray a couple of miles from my residence. Especially since my butler seems to have wandered several thousand miles from his.’ He nodded abruptly, then laughed. ‘You gave me quite a turn though, I don’t mind admitting.’ Kenilworth confessed in a stage whisper. He replaced his drink on the table.

Atkins glanced round for the Doctor. For a moment he felt panic welling up in the pit of his stomach. The Doctor was gone. Then he realized that the Doctor had followed him over to the table and was standing beside Kenilworth’s chair.

Kenilworth seemed to notice the Doctor at the same instant. ‘Who the devil are you, sir?’ he asked, quickly gathering up his papers and maps.

Atkins snatched the whisky from the top of a map just before the paper it rested on was pulled away. He carefully set it down again on the bare table top. ‘This gentleman, sir,’ he told Kenilworth, ‘has a proposition which I believe you will find of interest.’

‘Does he indeed?’ Kenilworth craned back to get a good view of the Doctor’s

face. ‘Well. sir, out with it.’ He shielded his eyes from the setting sun and

continued to stare at the Doctor standing over him. ‘What proposition is it that

causes you to hijack my man and bring him half across the globe?’

Page 3

The Doctor blinked, exchanged a look with Atkins, and stuffed his hands into his trouser pockets. ‘You are looking for a tomb,’ he said eventually. ‘A blind pyramid south of Saqqara.’

Kenilworth flinched visibly. ‘How do you know that?’ He turned to cast an accusing stare at Atkins.

Atkins began to shake his head in denial, then changed his mind. There was no point in prevaricating. ‘I think you should listen to the gentleman, sir. I have good reason to suspect he can provide useful information.’

Kenilworth reached for his drink. His expression suggested he was not convinced.

‘Mister Atkins is right, Lord Kenilworth,’ the Doctor said quietly.

‘Really? And what information, pray, can you provide me with?’

‘You must be prepared for some hardship, I’m afraid.’ the Doctor had been leaning forward towards Kenilworth. Now he straightened up. ‘There will be danger, death even, ahead of us. But if you’re agreeable I can offer my services to your expedition.’

‘And what exactly are you offering?’

The Doctor turned and looked out of the window towards the pyramids. He seemed to be considering his next words, and Atkins realized that this was the point where he had to decide if he was going through with his plan, when he had to decide that this really was the best course of action.

At last the Doctor answered Kenilworth. ‘I can lead you to the tomb,’ he said quietly.

Page 4

By the time Tegan was formally introduced to Lord Kenilworth, he was the bluff, avuncular man she had already met. He had taken to the Doctor as soon as they started to examine the maps and trace possible routes for the expedition. He found himself sucked into the Doctor’s obvious enthusiasm, and impressed by his intelligence and insight.

Before long, an outline plan had evolved and Kenilworth was busily giving instructions to Atkins to relay to the Egyptian bearers concerning provisions and scheduling. Tegan dithered on the edge of the discussions. She had glanced at the maps and the pencil marks showing possible routes and stopping points. But since she already knew where they were going and what they would find, she had found it hard to maintain an interest.

She sat alone at a table in the corner of the room and watched the sun edge its way below the silhouettes of the pyramids. Outlined sharply against the light, they seemed unchanged from the pristine, gleaming structures she had seen the day before. Or three thousand years previously, depending on your point of view, she reflected. Now, if she could make out details, she would see that they were pitted and scarred. The earliest man-made stone structures in the world were showing their age.

By the time the discussions broke up, Tegan was feeling tired, bored, and old. Atkins was charged with assembling the members of the expedition for a meeting at eleven the next morning, and Kenilworth debated whether to have one last night-cap for so long that the barman brought him a whisky to keep him company while he made his mind up.

The Doctor crouched down beside Tegan and pressed a hotel room key into her palm. ‘Get some sleep. Tomorrow will be a long day.’

‘It seems like it’s a long life,’ she told him.

The Doctor smiled broadly. ‘You’re telling me,’ he said.

Page

5

The huge metal blade swung in a slow arc above Tegan’s head. But the intense midday heat was hardly alleviated by the large ceiling fan. She sat at the back of the bar with the Doctor, wishing she had insisted on bringing clothes more designed for the climate than for the period.

Kenilworth was standing at the front of the room, one foot resting on the brass rail round the base of the bar. Everyone else sat round tables nearby, listening intently as he went over the outline arrangements for the expedition.

Tegan looked round her new colleagues and tried to remember their names as Kenilworth recapped on the details of the previous evening’s discussions.

Nearest to the bar was the ever-attendant Atkins. He sat almost to attention, back rigid and straight, paying close attention to every syllable.

At the next table sat Russell Evans and his daughter Margaret. Evans was a pale, thin, greying man in his sixties, every bit as doddery as Tegan had imagined a Victorian representative of the British Museum would be. His daughter was of an uncertain age, probably in her early thirties. She was dressed in dowdy tweed despite the heat, her hair tied in a tight bun from which auburn strands struggled to escape. Her features, Tegan decided, would have been attractive had they not been so severe.

Behind Margaret was Nicholas Simons, Evans’ assistant. He was young and

enthusiastic, taking copious notes of everything Kenilworth said, scribbling

them in a small leather-bound pocketbook. Between sentences he chewed nervously

on the end of his stubby pencil, and tried to ignore the glances Margaret Evans

threw his way. Tegan wondered whether he realized what was going on, or whether

he was simply unnerved by anyone looking his way. She spent a few minutes trying

to catch his eye and was eventually rewarded with his fleeting expression of

panic and renewed scribbling. Margaret Evans glared at Tegan, who smiled

innocently in reply before turning her attention to the next table.

Page 6

Here sat a figure whom Tegan had at once recognized from Kenilworth’s unwrapping party, although he did not know her or the Doctor. It was James Macready, an old friend of Kenilworth’s who had apparently accompanied him on several previous expeditions. He was probably about Kenilworth’s age, approaching fifty. In contrast to his friend he was a small man with little round glasses and thin grey hair. He nodded almost continuously and stoked away at a pipe which he never quite got round to smoking. Occasionally it approached his mouth, only to be waved in an approving gesture as Macready nodded again.

Opposite Macready was the head of the Egyptian bearers, Menet Nebka. His men would carry the bags, coax the camels, set up camp, and do the actual excavation. It had struck Tegan that really they could have mounted the entire expedition without their British employers. But since they were entirely motivated by the money, there would hardly have been any point. On an expedition grounded in uncertainties, their wage was the only constant.

Kenilworth laughed loudly at some joke of his own, and was rewarded by a few

nods and smiles from the assembled group as they made their way from the room.

Tegan grinned her approval, wondering what she had missed while she had been

looking round. She would ask the Doctor later, except that she suspected he had

been paying as little attention as she had. She followed them out into the heat

of the desert sun.

Page 7

The journey took three days. For Atkins it was three days of relief from the confusion and excitement of his trip with the Doctor and Tegan. It was also rather more stimulating to be planning the details of the expedition with Kenilworth and Macready than arranging the domestic arrangements at Kenilworth House with Miss Warne. Though he was surprised to find that he rather missed the housekeeper’s company.

The Doctor, for all his expertise and pre-knowledge, took a back seat. He seemed content to be carried along and organised by the others, making only occasional comments and suggestions now that he had shown Kenilworth the point on the map for which they were aiming.

Tegan was even less interested in the arrangements than her companion. But Atkins was not surprised at her frequent comments concerning the length of the journey, the heat, and the rate of progress. She complained almost as much as Nebka’s bearers.

Atkins leaned forward in his saddle to examine the map which Kenilworth was holding. His Lordship steadied his camel, and drew a finger along the path of the route still to be traversed.

‘Another day,’ Kenilworth said. ‘We’ll camp here,’ he pointed to a small blank area in the middle of the large blank area of the featureless paper that purported to be a map of the area. Atkins and Macready both nodded agreement, and Atkins pulled his camel round and set off back down the line of camels. He passed the word as he went: ‘Another two hours, then we’ll set up camp. We should reach the excavation site by noon tomorrow.’

‘Thank goodness for that,’ Tegan replied, struggling to prevent her camel

from sitting down and giving up on the spot. She pulled violently on the

harness, and it bucked, almost throwing her off. Then it turned its head slowly

round and spat at her.

Page 8

‘They will be at the pyramid by midday tomorrow.’

Sadan Rassul lowered his binoculars, taking care not to catch the light of the sun on the lenses as he did so. The two Egyptians behind him showed no sign of having heard him, but since the words were mainly for his own benefit, he was not worried. He crawled back from the edge of the sand dune, stood up and started down the slope towards where they had left the camels.

The two Egyptians turned to follow their master. If they smiled, it was because they knew their real work would soon begin.

The Doctor and Tegan had adjacent tents at the back of the camp. Tegan was less than impressed with her accommodation. It did keep out the sun but not the heat. And at night, it let in the freezing cold. There was barely room for one person inside, yet frequently either Macready or Evans insisted on visiting to see how she was coping with the adverse conditions. If she was lucky, she saw the Doctor once a day. But most of the time he spent alone in his own tent, apparently asleep. Tegan suspected he was actually thinking and calculating options and possibilities. Unless he really was asleep, of course.

Simons never came near Tegan, which she assumed was partly out of a nervous

sense of self-preservation, and partly as Margaret Evans rarely let him out of

her sight. Atkins was always too busy, though he greeted her with characteristic

politeness and a stoic lack of emotion on the rare times she ventured into the

burning sunlight to see how the boring process of carrying sand from one place

to another in wicker baskets was going. On these occasions, Lord Kenilworth

always made time and took trouble to include her in discussions and to enthuse

about how well things were going. The only way Tegan could see that progress was

judged was by the relative sizes of the pile of sand and the hole in the desert

floor at the base of the high sand dune.

Page 9

It was on one of those rare occasions when the Doctor was with Tegan, listening as ever to her complaints about the weather and the level of local entertainment, when Atkins arrived. He stood politely in the entrance to the little tent and waited for the end of the conversation.

‘Hello, Atkins,’ the Doctor smiled.

Tegan glared.

‘Good afternoon to you both,’ Atkins replied. ‘His Lordship wonders if you would be good enough to join him at the excavations.’

‘Who? The Doctor?’

‘He asked me to convey his compliments to you both, Miss Tegan. He thought you would be interested too.’

‘I’ve seen enough sand to last a lifetime, thank you.’

The Doctor cleared his throat. ‘I don’t think it’s sand that Lord Kenilworth is interested in showing us,’ he said. ‘Is it, Atkins?’

‘Indeed not, Doctor.’

‘What then?’

‘Nebka’s men have uncovered the entrance to the pyramid.’

Page 10

The short tunnel into the desert floor made the dune seem even higher. A wall of sand towered over the Doctor, Tegan and Atkins as they approached the excavations. The entrance mouth was wide, narrowing as it burrowed beneath the sandy hillside.

It looked as if the opening disappeared into total darkness. But as Tegan approached, the sun angled into the hole in the sand, and she could see that in fact the hole ended abruptly at a wall. And the wall was completely black.

Tegan shook her head and laughed. In her mind’s eye she saw the Doctor, four days earlier, looking round to get his bearings, then drawing a large X in the sandy desert floor with his index finger and saying ‘Dig there.’

The topography of the surrounding area had altered considerably. But Tegan could see now for the first time, with the huge pyramids of Giza outlined on the distant horizon, that they were back at the point they had visited thousands of years in the past. With a precision that anyone unfamiliar with the Doctor’s casual expertise would have found difficult to believe, the excavations led directly to a buried black marble door. The door that led into the pyramid where Nyssa was entombed.

‘You were right, Doctor,’ Kenilworth said loudly as he greeted them. ‘Incredible. I’d love to know where you get your information.’

The Doctor smiled. ‘Years of research,’ he said. ‘Many years.’

Before Kenilworth could comment, there was a cry from the tunnel. It was

followed quickly by another shout and before long a loud chorus of voices was

jabbering away in Egyptian.

Page 11

‘What is it now?’ Kenilworth asked angrily. ‘They’ve done nothing but complain ever since we got here.’

Atkins set off to investigate. While he was gone, Macready joined them and he and Kenilworth complimented the Doctor again on his wisdom and expertise. By the time Atkins returned, Tegan was sick of hearing how clever the Doctor was. She was firmly of the opinion that the last thing one should do with an appreciation of the Doctor’s undoubted brilliance was to tell him about it. And the Doctor’s smug and insincere denial of his own genius was the most annoying aspect of the whole experience.

‘Well, what is it?’ Macready asked when Atkins returned.

‘A religious problem, sir. It seems that they have uncovered some hieroglyphs around the entrance that are rather worrying to their somewhat superstitious outlook.’

‘Really?’ the Doctor said. ‘What hieroglyphs are those, I wonder?’

‘It seems to concern several variations on the symbol which represents the Eye of Horus, Doctor.’

‘Indeed,’ Kenilworth seemed resigned to the problem. ‘Very well then. I suppose we shall have to take the usual action.’

‘What’s that?’ Tegan asked.

‘First we agree to reduce their onerous duties,’ Atkins replied.

‘Not really a problem, since we shall want to open and examine the pyramid ourselves,’ Kenilworth pointed out.

‘And then,’ Atkins continued, ‘we offer them more money.’

Page 12

Despite the offer of increased wages, and Kenilworth’s insistence that once the main door was open they could retire to their tents, the Egyptians refused to do any more work. The Doctor paid little attention to the negotiations, and Tegan kept him company as he examined the doorway.

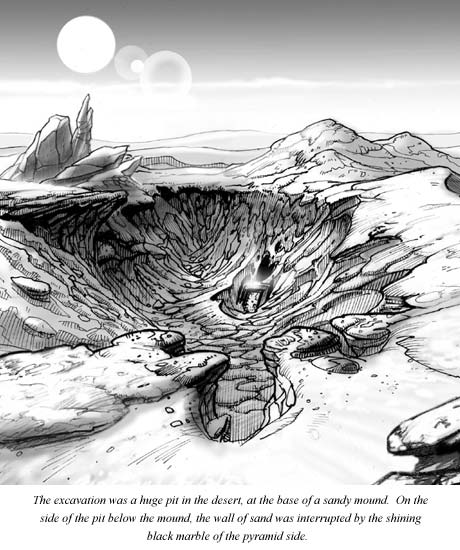

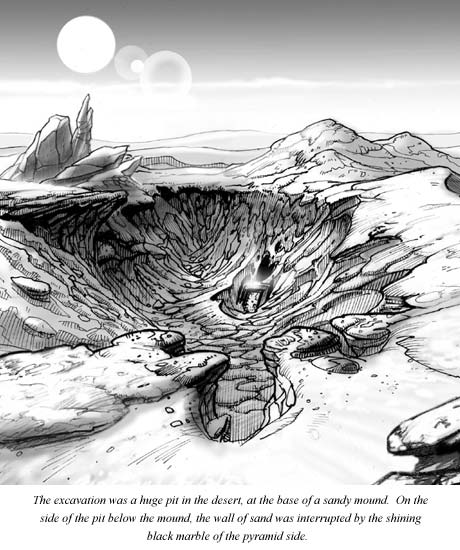

The excavation was a huge pit in the desert, at the base of a sandy mound. On the side of the pit below the mound, the wall of sand was interrupted by the shining black marble of the pyramid side. It sloped back into the sand above, revealing little more than the high doorway. The stone was still smooth and polished, which the Doctor suggested indicated either that the pyramid had been buried for much of its long life, or that it was constructed of incredibly durable material. Or both.

Around the doorway, hieroglyphics were carved into the black stone. As Tegan shifted position, the sun caught them and darkened the blackness in the cuts that formed their shapes. They were difficult to make out - darkness in the blackness - but the symbol the Doctor had pointed out as the eye of Horus was repeated several times.

‘It’s sprung,’ the Doctor said thoughtfully after a while. He stood back and framed the doorway between artist’s hands, peering through the window between his thumbs and index fingers. ‘There must be more to it that that,’ he said after a while.

‘Why?’

‘What?’ he seemed to have forgotten Tegan was with him. ‘Oh, too straightforward. That’s why.’ He pushed experimentally at a point on the door about a third of the way up its nine-foot high edge. ‘If it were that simple,’ he said as he exerted more pressure and gritted his teeth, ‘you could just do this.’ He stepped away and waved a hand at the door to show the futility of his actions.

And with a rumble of stonework, age, and weight, the heavy door opened slowly

outwards. The Doctor’s smile froze on his face. ‘I don’t like that,’ he

muttered.

Page 13

The light from the oil lamps glistened on the stone walls and danced across the flagstones of the floor. They crowded into the narrow passageway, looking along the long corridor as it sloped upwards into the pyramid with a mixture of awe and apprehension. Tegan could feel the tension in the air, a tightness that might precede a thunderstorm.

Kenilworth led the way, the Doctor close behind with Tegan. Atkins and Macready were close on their heel, with Russell Evans and his daughter beside them. Simons brought up the rear, glancing up now and then from his pocket book as he scribbled frantically.

‘First dynasty?’ Macready suggested, and Evans nodded his agreement. Simons flicked over another page.

‘I think that is where we are heading,’ Kenilworth said eventually. He raised his lamp above his head, and pointed towards the end of the long corridor.

Tegan could just make out another doorway. It was filled with a pair of huge double doors, the handles tied with frayed and rotting cord. She took a step towards the doors, and gasped out loud.

Kenilworth’s lamp cast its light sideways as well as forwards. As Tegan

moved, she saw that the light was illuminating what had been a dark patch of

wall beside her. Now she could see that it was an alcove. And in the alcove

stood a woman. At once Kenilworth and the Doctor were at Tegan’s side. She gave

a sigh of relief and shook her head in disbelief at her own nervousness. The

woman was a statue, her twin looking across the corridor at them from an

identical alcove on the other side.

Page 15

‘Remarkable,’ breathed Kenilworth, stepping aside to let Evans and Macready take a closer look. The Doctor frowned in the lamplight, and Margaret Evans shuffled closer to Simons.

The statues were life size. The woman they depicted was strikingly beautiful. She was tall and slim, her dark hair folded up on to her head in a cloth headress. Her features were aquiline, and her eyes large and cat-like with huge pupils. She was dressed in a simple robe which reached to her knees. If it had once been white, it was now discoloured with age and dust.

‘Shabti,’ Atkins said quietly to Tegan.

The Doctor nodded, and seeing Tegan’s puzzlement said: ‘Shabti figures were put in the tomb to serve the dead. The Egyptians assumed that there would still be work to be done in the afterlife, so they provided servants to do the washing up.’

‘Indeed,’ Atkins agreed. ‘Not all were life size. Some were just small dolls.’

‘But,’ the Doctor said, leaning close so Tegan could see his significantly raised eyebrow, ‘they were usually in the image of the person buried in the tomb.’

Tegan looked back at the figure in the alcove. Evans, Macready and Kenilworth were examining a detail of the carved fingers. Evans traced a finger over the woman’s ornate ring and pointed to a bracelet carved on to her wrist.

‘She doesn’t look like Nyssa,’ Tegan said.

Page 16

‘Not even close,’ the Doctor agreed.

‘Perhaps a stylised representation?’ Atkins suggested.

The Doctor shook his head. ‘No. Too tall. The features are completely different, and the, er -’ He struggled for a suitable phrase, carving a female figure in the air with his hands.

Tegan let him flounder for a while before coming to his assistance. ‘The bust’s too big,’ she said. ‘But why all the interest, anyway?’ she continued before Atkins could react. ‘They’re just wooden statues.’

Whatever scathing response about the figures’ preservation, workmanship and archaeological importance the Doctor was about to deliver was curtailed. He and Atkins stood gaping at Tegan. Before she had time to ask what the problem was, the Shabti figures stepped out of their alcoves and into the corridor in front of her.

Everyone started talking at once. Margaret Evans screamed and clung to Simons, which seemed to surprise him even more that the Shabti. The others drew back along the corridor, with the exception of the Doctor.

‘Fascinating,’ he said. ‘You know, I doubt there’s any real danger.’

Then the door at the entrance of the pyramid slammed shut. Everyone fell

silent, exchanging frightened and puzzled glances in the flickering torchlight.

Page 17

The voice was melodic, almost musical. It resonated within the corridor, seeming to be born out of the air itself. ‘Intruders, you face the twin guardians of Horus.’

Tegan looked round. The voice seemed to be coming from above, from the corridor ceiling, or an upper floor of the pyramid, but she could not be certain.

‘The corridor is now sealed, and has become a Decatron crucible. The answer you will give the guardians controls your fate - instant freedom, or instant death. Where is the next point in the configuration? This is the riddle of the Osirans.’

The sound echoed off the stone walls for a split second after the words were finished. There was silence for a while.

‘Doctor?’ Kenilworth said eventually. ‘What does it mean?’

‘It means we’re in trouble. The corridor is in effect an airlock, and they can pump out the air, or unseal the entrance, depending on our answer to the riddle.’

‘But what riddle?’ Macready asked.

The Doctor smiled. ‘Let’s ask, shall we?’ He strode up to the two Shabti figures and inspected them closely. ‘Now then, I assume you two have a question for us.’

In response, the two female statues raised their arms in unison. As they did

so, the ceiling of the corridor glowed into life, small squares pulsing into

brilliance on the illuminated background. A curved line cut across the roof, the

squares of light arranged along the right side of it.

Page

18

‘Just as I thought,’ the Doctor said with a nod. ‘Thank you.’ He turned back to the others. ‘Now all we have to do is work out the next point in the configuration.’

‘But what’s it a configuration of?’ Tegan turned her head sideways to try to make sense of the image.

‘Well, if we knew that there’d be no riddle.’

Kenilworth craned his neck to see. ‘It does look vaguely familiar.’

Macready and Evans both nodded.

‘I’ve seen it somewhere before too,’ the Doctor admitted. ‘Wish I could remember where.’

At the back of the group, Simons began to copy down the image into his notebook. Tegan could see him framing it up and checking he had the proportions approximately correct. The snake-like ribbon curled down the left side, and several squares were arranged to the right. The three most central were almost aligned. But the top one was offset slightly to the left. Three squares were apparently randomly arranged to the left of the central cluster, two to the right.

Simons stared at what he had drawn, then back at the high ceiling. ‘It’s a

map,’ he blurted out in surprise.

Page 19

Tegan was not convinced, but Atkins was nodding thoughtfully beside her.

‘Good grief,’ Kenilworth said. ‘And we all know what of.’

‘Do we?’

‘The thick line curling down the left is the river Nile,’ Atkins explained. ‘The squares are the major pyramids.’

‘Of course,’ Evans was standing on tiptoe to get as close as possible. ‘This is fascinating. Look Margaret,’ he waved his hand at the roof, nearly losing his balance. ‘This shows the main pyramid complex at Giza, plus the pyramids at Abu Ruwash and Zawyat-al-Aryan.’

Margaret seemed less impressed. ‘So what is the next point?’

Macready addressed them all. ‘That, I think is a problem. These points mark the positions of the greatest pyramids, the first rate ones, if you will. Each of them is marked.’

‘So we need to show where there’s another first rate pyramid,’ Tegan suggested.

Macready shook his head. ‘As I said, Miss Tegan. Each of them is marked. There are no other points in the configuration.’

‘Unless,’ Kenilworth said, ‘there is one we don’t know about.’

‘Yes, that’s possible isn’t it? Why not this pyramid?’

Page

20

The Doctor coughed. ‘This pyramid is minuscule by comparison to those. And he’s right Tegan - there are no more pyramids of that scale to be found.’

‘Great. Terrific.’

‘So,’ the Doctor said, ‘I suggest we turn our attention to this.’ And he turned to indicate an illuminated section of wall behind them.

The hieroglyphs meant nothing to Tegan, but the more learned members of the party swarmed over them. After ten minutes the noise had subsided and everyone was back to staring glumly at the wall.

‘Can’t they read it?’ Tegan asked the Doctor quietly.

‘Oh yes. That’s the easy bit. It’s a series of eight numbers, starting at seventy and finishing at twenty-three hundred. The values in between seem to be random. At least, they don’t conform to any pattern or sequence I can think of.’ He leaned forward. ‘And I can think of lots,’ he added.

Tegan grunted. ‘Well we should thank our lucky stars you’re here then.’ She looked back at the glowing ceiling and the silent figures standing motionless below, arms raised as if in adulation. ‘Who are these Osirans, anyway?’

‘Hmm? Oh a super-powerful race from the dawn of time. They come from Phaester Osiris, which is -’ The Doctor broke off. ‘Of course, I should have realised.’ He clapped Tegan on the shoulder so hard it hurt. ‘You’re brilliant.’

‘I am?’ She was not convinced.

Page 21

But the Doctor was already gathering everyone round. ‘Right, I think I’ve got it, with a little help from Tegan. It is a map, and the figures are distances. But it isn’t a map of Egypt.’

‘Not of Egypt?’ Macready was surprised. ‘Doctor, you can see for yourself how accurate the positioning of the pyramids is.’

‘Exactly. But this is a map of the geography from which the pyramids’ positions are copied. Look, see how the line of points in the middle is slightly skewed, with the topmost point slightly left of true.’

Kenilworth was shaking his head. ‘It’s baffled scholars since Napoleon’s time that the later pyramid is smaller and is not on the line of the other two, Doctor.’

‘Precisely. Why would any Pharaoh build a pyramid smaller than his predecessors if he didn’t have to? And why not continue the line so incredibly accurate between the first two?’

‘All right,’ said Tegan, ‘why?’

‘Because the pyramids themselves are a map.’ The Doctor pointed up at the ceiling. ‘That isn’t the Nile,’ he said, ‘it’s the Milky Way.’

‘What?’

Page 22

‘And the points are the stars in the constellation of Orion. Rigel, Mintaka, Betelgeuse...’ the Doctor reeled off the names as he pointed them out. ‘The numbers are the distance of each from Earth in light years, or more importantly the distance a thought can travel in a year, which is pretty much the same thing. Rigel, for example, is nine hundred light years away. And the three points almost aligned are what you know as Orion’s Belt.’

‘Then where is the next point? What star is missing?’

‘Like the pyramids, I’m afraid, they are all there.’ The Doctor thought for a while. ‘Orion was important to the Osirans, and hence to the ancient Egyptians. The Osirans taught them all they knew, after all.’

Evans and Macready were exchanging looks which suggested they thought the Doctor was insane.

‘Go on, Doctor,’ Tegan encouraged, glaring at Macready.

‘Well, it’s something to do with a power configuration. Looping stellar activity through a focus generator and aiming at a collection dome. Or rather pyramid, knowing the Osirans. I’d say the final point in the sequence is Phaester Osiris itself.’ The Doctor drew an extendible pointer from his top jacket pocket. Tegan wondered if he was about to continue his lecture with slides as he pulled it to its full extent. But instead he pointed it at the corridor ceiling.

A point of light flared into existence as the rod touched the stonework. The final point in the sequence.

‘Of course,’ Kenilworth said. ‘The great Sphinx.’

Page

23

But before anyone could comment, the twin Shabti figures lowered their arms and stepped aside. The ceiling dimmed, and the glowing section of wall faded back into the stonework. Far behind them, the main door clicked open and remained ajar, a thin line of daylight forcing its way into the passage.

‘These Osirans - ’ Kenilworth started.

‘Time for that later, Kenilworth,’ Macready pointed to the far end of the corridor. ‘The tomb!’

They made their way warily along the rest of the corridor, scanning the walls for other alcoves or figures. But they reached the double doors without further incident. Macready had a pocket knife open, reaching for the red cord which bound the door handles. Simons was head down again scribbling in his book and keeping a safe distance from Margaret Evans.

‘Er, I wouldn’t be so hasty, if I were you,’ the Doctor warned, tapping Macready on the shoulder.

‘Nonsense, man.’ He continued to pull at the cord with the knife blade. ‘Nearly through now.’

Tegan stood arms folded with the others, clustered round the doorway. Light

strobed across the face of Macready as he hacked at the rope, and Tegan looked

round puzzled trying to locate its source. The effect was regular, not like the

flickering of the torchlight.

Page 24

‘Doctor,’ she said. ‘The light.’ And then she saw the source, and pointed to the stylized eye glowing in the floor at her feet.

‘The Eye of Horus,’ Atkins breathed.

‘Stop!’ the Doctor shouted as Macready cut through the last strand of the cord and pulled open the doors.

The eye flashed brilliant red as the hurricane swept down the corridor. The Doctor had grabbed everyone he could as he dived for cover. Macready was holding on to the door handle, braced against the rushing force of the air as it was forced past him. Tegan grabbed Margaret as she was blown past, and pulled her down to the ground.

Simons, still scribbling in his notebook, had reacted slower than the others. He was caught full in the blast and hurled down the corridor, bouncing down the slope and crashing into the walls. His book burst apart in a frenzy of whirling paper, pencil clattering across the floor. He rebounded from the wall and slammed into the ground, head cracking open on a flagstone. A dark trail followed his body as it was tossed like a ragdoll along the passageway.

Tegan kept low, feeling the force of the wind tugging at her short hair, as

it struggled to dislodge her. She felt her grip on Margaret slipping, and fought

to keep hold. Out of the corner of her eye she could see the Doctor holding

Atkins and Kenilworth back with one arm, and holding firmly to the doorpost with

the other. Beyond him the doors to the tomb stood open.

Page

25

From his vantage point, Sadan Rassul watched the door to the black pyramid blown open and the pages of Simons’ book blasted into the heat of the day. And he smiled.

London, 1986

Rejected Applications

10557/86 Structural alterations and renovation

of grade two listed domestic residence. See full application for details and

appendix 2B for reasons of rejection.

The British Museum, London 1996

Henry Edwards swept his torch round the darkened room once more. The beam of light glanced off the polished floor and strayed over the tables of relics. It peered into corners, and licked round the feet of a sarcophagus standing against the far wall.

Edwards closed the door behind him, and for a moment the light from his torch continued to stray under the door. Then all was dark again.

A faint glow in the corner accompanied the crashing vibration of sound which echoed through the room. The glow resolved itself into a flashing light as a shadowy form solidified beneath it. The ground to a halt, and the TARDIS door opened tentatively.

The Doctor’s head appeared round the door for a moment. Then it disappeared

again. A few seconds later, the Doctor stepped into the room. He was holding a

lantern. He made his way from table to table, letting the pale light pool around

him as he examined and then discarded various vases and jars. He shook his head

in annoyance and exhaled loudly. ‘Should have paid for a catalogue,’ he

murmured.

Page 26

He looked round for another display of relics, and set off towards the door. As he passed close to the sarcophagus, his foot caught something, sending it into a spin. Standing on the floor, close to the sarcophagus, was a canopic jar. The Doctor knelt down, catching the jar as it continued to wobble on its uneven base. He patted the top and stood up again.

Then he frowned, and bent down to examine the jar once more. The stopper was carved into the shape of a jackal’s head. The Doctor lifted the jar and held the lantern close to it. He sniffed at it, shook it, then turned it over to see the base.

‘That should do nicely,’ he said quietly. ‘An Osiran generator loop, rather the worse for wear, but it should do very well indeed.’

The Doctor stood up, hefted the canopic jar in his hand, and smiled at the

jackal. Then he went back inside the TARDIS. A short while later, that too was

gone.