BBC Cult - Printer

Friendly Version

Human Nature - Chapter Five

Page 1

Hurt/Comfort

Excerpt from the writings of Dr John Smith

So for what season or circumstance was I built? My thumbs are useful, my appendix, which hurts sometimes as if newly made, is not. Sometimes it feels as if I'm bigger on the inside physically, too. Joan told me that the Latin I failed to understand referred to that. The school motto refers to the relative dimensions of books. I like that. If you could see information, a book would be like a pin-cushion in your hand.

Still haven't found Gallifrey on the map. Maybe I made it up?

Excerpt from a letter written by Joan Redfern, date unknown

I'd forgotten. It was like a sleeping tiger, and it was suddenly awake and upon me again. And it was beautiful.

As darkness fell across the valley below, Benny and Constance were walking up a narrow lane, past badger sets and through thickets of stinging nettles that Benny had to swat aside with a stick taken from an old elm. They were climbing up to the wooded hillsides, Benny realized, heading in the direction of the statue of Old Meg.

During the walk, while Constance was silent, Benny had come close to

despairing. There'd been no sign of the aliens, if that was what they were.

Perhaps the reason that the Pod was gone was that they'd found it and gone too.

Page 2

She and the Doctor would be trapped here, and she'd have to find a way to survive when the money ran out. Perhaps Alexander would give her a job. At least she could sleep in the TARDIS. If the aliens had the Pod and hadn't left, mind you, the only option was to get it off of them by force. Now, that would be really difficult.

'Have you got arms dumps all over the place?' she asked Constance.

'Yes. Asquith doesn't show any signs of budging, so we're going to start blowing a few more things up.' The young woman had struggled valiantly up the hill, hitching her skirts as they went.

'What if a war starts and other people start blowing things up?'

'A war? With whom? I mean, it looked as if the Germans were going to have a pop a few years ago, but that's all calmed down. Churchill's started to dismantle the Navy, and they're doing likewise. No, it's only now, now that there are no more wars to be fought in this world, that we can really do something about our situation. Asquith thinks he can sleep easy, bar Ulstermen or Anarchists, but he hasn't reckoned with us.'

They'd reached the top of the hill. Benny helped Constance step over a stile, and they walked over to the statue. The old woman sat proudly on a stone chair, her bag clasped in her stone hands, looking down at the valley.

While Constance started to examine the back of the chair, Benny glanced down at the town below. Comfortable lights had popped up all over and the smoke of evening cooking was drifting from chimneys. A line of white steam marked the passage of a train along the branch line; she could just hear its sound in the distance, the regular beat of humanity at peace.

She thought of scarlet explosions, for a moment, of beams bursting across the

valley, reducing the town to rubble in seconds. Actually, now that she'd got

that picture in her mind, something about the valley fitted. A slow trail of

brown smoke was drifting from the hospital, which still had a fire engine

standing beside it. She shivered.

Page 3

Constance was examining the base of the statue. 'We'll need a lever of some kind. What about your stick?'

'I can do better than that.' Benny unfolded a lightweight plastisteel crowbar from her jacket, pushed it into the thin gap between one of the stone panels and the surrounding masonry, and heaved. After much shoving, with Constance's help, the panel came away and fell to the ground. Inside the block were a number of sticks of industrial dynamite, packed in straw with long taper fuses. 'If only Ace were here,' said Benny, frowning at the primitive explosives.

'Who?'

'Absent friends.' Benny reached inside and grabbed a bundle. It was sticky. 'I know nothing about this kind of thing, but this doesn't feel very safe. How long have you had it here?'

'Ever since I stole it from a quarry. The first time I was let out of prison and came down here on holiday, that was, oh, eighteen months ago?'

Benny sucked in a breath, and carefully put the dynamite back. 'I think that's going to be more trouble than it's worth.'

'As you wish.' Constance watched as Benny replaced the panel at the statue's base. 'Is your motive for seeking a weapon purely revenge?'

'Hardly. A friend of mine's in trouble. I have to find a certain object to help him.'

'And where is this object?'

'Ah, that's the question, isn't it? I have a terrible feeling that I know who's got it. In any case, I'm in a bit of a pickle.'

Constance checked the edges of the replaced panel of masonry and straightened

up. 'You're not in a pickle at all. Where were you planning on staying this

evening?'

Page 4

Benny knew the answer to that instantly. She'd steeled herself for another night in the woods, already welcoming the idea of being alone like a boxer welcomes the first punch. But Constance gave her a little more heart. 'Perhaps there is somewhere. The house of a friend. If I tried to take that little lot down there, I think I'd explode on the way.'

'I'll go with you.' Constance took Benny's arm and carefully allowed herself to be led down the hillside. 'If I cannot provide you with weapons, at least I can manage moral support.'

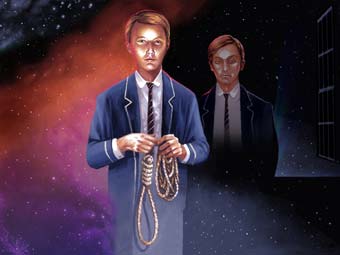

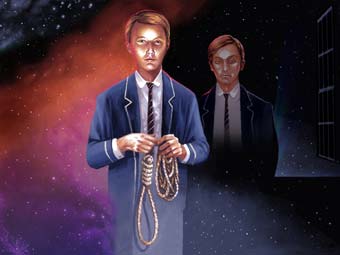

'The court martial will come to attention.' Hutchinson banged the gavel on to the three bedside tables that had been lined up in front of him. Tim stood on a bed facing him, a horrified expression already on his face. The other boys stood in a circle around him. 'The case is the crown against Timothy Dean. The defendant is charged with being a bug, and allowing his just punishment to be ignobly deferred by a master. How does the defendant plead?'

Tim stared at the circle of boys. 'I... I don't.'

They laughed. Hutchinson banged his gavel. 'Guilty or not guilty?'

'I'm neither. Or both.' His voice was a whisper, but it seemed to echo from every corner of the dormitory. 'If you're trying me, then you'll decide, won't you?'

'Then another charge is added,' Hutchinson decided. 'Contempt of court and of British justice. Let us first hear from the prosecution.'

'My lord,' Merryweather stood up, a dish rag on his head, clutching the lapel

of his blazer, 'the prosecution's case is that Dean, through the extraordinary

protection of one Dr Smith, managed to get out of a simple slap with the

slipper. This can't be allowed to pass. The implications for discipline are

terrible. I move that Dean suffer the fullest possible punishment, and will

prove that this is most deserved. I call no witnesses, since I believe my case

is proved by one look at the defendant's buglike features.' He sat down.

Page 5

'And now the council for the defence,' said Hutchinson. 'Let us hear from Dean's best friend, Darkie Unpronounceable.'

Anand looked up from his uneasy place in the circle.

He'd kept his gaze to the ground previously, embarrassed that he was part of this idiocy.

'Darkie Unpronounceable!' Hutchinson repeated, looking searchingly around the circle. 'If there is no defence, then we shall proceed straight to the sentence.'

Anand heaved a heavy sigh. 'I'm - '

'No!' Timothy cried. Suddenly, all eyes were upon him. 'There's nobody here called that. I'll defend myself.'

'Very well!' Hutchinson beamed, thumping down his gavel. 'What do you have to say for yourself?'

Timothy paused, considering. When he spoke, his voice quivered with fear. If only he'd let Anand defend him. Lately, his thoughts seemed to be full of danger like this, leading him into all sorts of awkward comers. 'I'm sorry that I didn't hear Dr Smith yesterday. It won't happen again.'

'Well, that's all very well,' began Merryweather, 'but there's the matter of - '

'It's just that I've been having these dreams,' Tim continued, oblivious, his voice a whisper that echoed around the wooden comers of the dormitory. 'They distract me. They're with me all day. I see you all die, over and over again. You're screaming, Captain Hutchinson, because you know that something's about to fall on you. Merryweather's only got one leg. Please... does anybody else have dreams like that?'

Hutchinson glanced at the other boys, a wide grin spreading over his face. 'I

think we're made of different stuff to you, bug. You can't scare us.'

Page 6

'I'm not trying to scare you. I'm just saying that I see it all the time, and it distracts me. That's my defence.'

Hutchinson nodded. 'Very well. What's the verdict of the jury? Hands up for guilty.'

All the boys put their hands up but one. Anand. Timothy smiled at him.

'So, guilty it is.' Hutchinson banged the gavel again. He reached behind him, and put a black square of the material used to repair school uniform on his head. 'I sentence Dean to be hanged by the neck until dead. Is the executioner present?'

Phipps raised his hand. In it was a noose made from gym rope. Timothy stared at it.

'You're joking, of course?' said Anand, looking between Timothy and the rope. 'You can't go through with it.'

'Shut up, darkie. Take him to the window.' The boys rushed forward, pulling Timothy off his feet and carrying him towards the window. Somebody pulled it open and propped it up. The noose was thrown around Timothy's neck, despite his weak protests. The other end of the rope was tied around the foot of a heavy wardrobe.

Anand turned and ran for the door, but a couple of boys grabbed him before he got there and sat on him, stuffing a handkerchief into his mouth.

Hutchinson leapt up on to the bed, swinging the cloth excitedly around his head. 'Executioner, do your duty!'

Phipps supervised the frenzied dragging of Timothy to the window-sill. The boys grabbed his arms, and aimed him like a battering ram for the gap between the window and sill. Chill winds blew in from the darkness outside. The rope swung from Timothy's neck, and he went limp, giving up his struggles.

Let them, the voice inside him said. Hang me, cut me down, spread my blood on

the field. End my life. I'll return.

Page 7

With a great rush, the boys threw Timothy out of the window. The rope unreeled after him, and then snapped taut.

They piled to the window and gazed out. Far below, Tim's body hung limp, swinging in the breeze, his arms dangling by his sides.

'He doesn't seem to have grabbed the noose...' Merryweather whispered.

'No,' Hutchinson agreed, his face absolutely still. 'He doesn't.' Then he yelled with sudden violence: 'Reel him in, for God's sake! Before somebody sees him!'

Benny and Constance stood outside the little red-brick museum. Benny was busy throwing stones at one of the windows above, not wanting to ring the little bell on the front door.

'So you are a friend of Mr Shuttleworth,' Constance whispered. 'I know him by reputation. He has some associates who are very active in the Labour movement, and they've been supporting our cause. Oh, there he is!'

Alexander, clad in a bath-robe, had angrily pulled up the window and glared down at them. 'What the devil? Oh...' He broke into a smile. 'Pardon my Greek. Be right down.'

They waited, crouched behind the hedge, for quite some time. Finally, Benny pulled out her watch and glanced at it. What's he doing in there?'

'He boasts, people say, of his several lady friends. Mr Shuttleworth seems to share Mr Wells' opinions on free love. What do you think?'

'Erm, I'm certainly opposed to paying for it. Should I feel nervous about staying with him?'

'Oh...' Constance seemed to consider for a few moments. 'Well, I have never

heard of him doing anything actually improper.'

Page 9

'What do his girlfriends say?'

'I haven't met any of them. He's apparently very circumspect.'

From the other side of the hedge there came the sound of tapping footsteps. Benny and Constance crouched down further.

Of course, it was just at that moment that the door opened and Alexander, now in smoking-jacket and trousers, stepped out on to his doorstep. To his credit, he didn't even glance in the direction of the fugitives in his garden, noting Bernice's anguished hand signals out of the comer of his eye. Instead he smiled at the young nurse who was standing in the road beside his gate, her head turning this way and that as if sniffing the breeze. 'Good evening, nurse. Can I help you in any way?'

The nurse turned and looked at him suspiciously. 'No, no, I was merely waiting for somebody. Perhaps you may have seen her. A lady of around my age in a checked skirt, perhaps in a state of some disarray.'

'Would she be...' his gaze flicked down into the garden, 'muddy?'

'Yes, that's her. She fled from the blaze at the hospital. I've been sent after her.'

'Yes, I was wondering what the to-do was over there. Is everybody all right?'

'Oh yes. A blanket caught fire, and it spread. The fire brigade quickly extinguished it. Now, I must hurry you. Where did you see the lady?'

Benny sneezed.

Alexander sneezed. 'Still a chill in the air. Sorry. I saw her pass this way about an hour ago. She went, erm, that way...' He gestured vaguely down the road. 'She was running.'

'Thank you.' The nurse lifted her skirts and dashed off in the indicated direction.

Alexander glanced down into his garden. 'You can come out now,' he called softly. 'A policeman I could understand, but how does one end up being chased by a nurse?'

Benny patted his shoulder as he showed her in.

'Wouldn't you like to know?'

Page 10

Smith leaned back in his chair, his arms behind his head. His writing was getting better. He hadn't wanted to go to bed when he came home. He was so full of emotion and energy. He felt reborn. He'd gone straight to his desk and started to scribble page after page of his children's story. He was rather proud of it.

The Gallifreyans eventually made a wonderful world for themselves, with towers and cities, lords and ladies. The inventor watched over them and advised them on how best to make their world as civilized and law-abiding as the England that he'd left behind.

But as time went on, he became discontented with the place. The Gallifreyans had taken his ideas far too much to heart, and they'd become boring and stuck-in-the-mud. He invented a way for them to start another life when they died, and gave them another heart, hoping that this would make them joyful and happy. But they were just as dull, and now they lived longer. Worse than that, they no longer had children, so there was nobody noisy around the place to ask questions.

Finally, he could take no more of it. He took one of the police boxes and headed back to Earth. The Gallifreyans would chase him, he knew, because he'd broken one of the laws that he'd invented.

But he'd decided that being free was better than being in charge.

There came a clatter from the window. He hopped up and opened it, and was surprised to see an owl sitting on a low branch outside, regarding him with disdain.

'Hello,' said Smith. 'And who are you?'

'Woo,' said the owl.

'How do you do, Mr Woo?'

'Who.'

'Who? You, Woo.'

Page 11

The owl, looking as flustered as an owl can get, opened its wings wide and flapped up into the air. Smith flinched and the bird flew past him through the window, settling on the mantelpiece of the cottage with a proprietorial air.

'Oh no,' Smith sighed. 'You can't stay here. There's no room. Why do you want to stay in a house, anyway?'

The owl didn't say anything. It just closed its eyes and turned its head away.

Smith looked at it for a few moments, wondering if he should try and lift it outside. The claws looked rather fierce for that. Finally, he just spread some newspaper under the mantelpiece and left the owl to sleep.

He returned to his writing table, and was just about to pick up his pen again to edit what he'd written, when there came a knock at the door. 'Could you get that, Merlin?' he asked the owl. No reply forthcoming, he went and opened it.

The door was slammed out of his grip.

Something dark launched itself through the gap and landed on his chest, pinning him to the floor.

'Silence!' it hissed.

Smith frantically reached for a poker that stood by the fireplace, but the lithe dark figure snapped a hand out. It caught Smith's fingers and wrapped them in its own gloved fist.

It wrenched Smith's left hand up to face level and the little schoolteacher caught a glimpse of glittering eyes and white teeth under the brim of the hat.

'Pleased to meet you, human!' snarled Serif. Then he bit the end off Smith's

little finger.

Page 12

Benny and Constance sat in the little back bedroom of Alexander's rooms above the museum. A heavy curtain hung over the small window. When Alexander had popped out to make the tea, they'd heard footsteps going downstairs. Unfortunately, the window was on the wrong side of the building to see who might be leaving.

'I'm getting positively used to hiding,' Constance sighed, leaning her head on Benny's shoulder. 'I wish, sometimes, that I could change the way I look, just magically transform into a bird, or a cat. Wouldn't that be wonderful, to change what you were just by thinking about it? Wouldn't you like to do that?'

'Not really.' Benny was wondering if this place had a bath. The mud was dropping off her and getting the bedclothes dirty already. 'I just want to be me and do that as well as I can.'

'But you could get into any dress you liked or be a man for a day and go out carousing.' She started to twirl the ends of Benny's hair absent-mindedly. 'You could do whatever you wanted. This sullied flesh could melt and resolve itself into a dew.'

Benny rubbed her brow, wondering why everything in her life seemed to happen at exactly the wrong time. She plucked Constance's hand from her hair and patted it comfortingly. 'That's a lovely idea, but it doesn't help me at the moment. Right now, I need to find this object I'm looking for.'

'Well, if you know who's got it, then in the morning you can just go and get it off them, can't you? I know all the back ways and side roads. With my help, it won't be hard at all.'

'I suspect it may not be as simple as that, but, yes, I'll meet you in the morning and you can give me some idea of the territory.'

Alexander bustled back in with glee, handing them each a mug of steaming tea.

'Goodness me!' he exclaimed. 'What excitement! Why was that nurse after you, do

you think?'

Page 13

'I have no idea.' Benny took a long swig from her mug. 'I don't know any nurses. Perhaps she's another one of this lot who are hunting me.'

'As you say. I mean, terrible for you, being pursued, but this is dreadfully exciting. Oh, I say, it's only just occurred to me. Bernice, you're wearing trousers!'

'Many people have already noted that, Alexander. I don't suppose you've got a bath, have you?'

'Oh yes,' said the effervescent curator. 'By sheer chance, I, erm, already had the boiler on. Was going to have one myself, after my lady friend had left, but your need is greater.'

'Wonderful.' Benny drained her mug in one lengthy gulp. 'Now, Constance, will you be all right getting to your own lodgings?'

'Of course.' The young woman finished her tea and stood up. 'I shall see you here at eleven, and then we shall reverse the roles we have so far played. Your persecutors shall be the prey, and we the hunters.'

'You know,' said Benny, 'when you say things like that, you almost make me feel confident.'

The dark man swirled in and out of Smith's vision, a fluttering phantom above him.

Pain was shouting distantly. Smith clutched his hand, astonished at the new shape of it. That was the thing about taking a wound, the unreasonable fact that a bit of you had gone.

Serif had chewed on the finger thoughtfully for a few seconds as Smith had

screamed, and then swallowed it. He put a hand to Smith's temple, and suddenly

the little schoolteacher found that he couldn't scream any more. Some part of

him wanted to reach down the creature's throat and take the lost part of him

back, but most of his thoughts were consumed by a sickening, flattening, terror.

He noticed, as his vision swirled randomly around the room, that the owl seemed

to have gone. Perhaps he'd only dreamed it. Serif spent several minutes just

sitting on his chest, concentrating. Finally he spoke.

Page

14

'I can taste who you think you are. Laylock did his work well. You are full of nanites, and if I had eaten more of you, they would start affecting me. This person you have made for yourself is quite fascinating. Shall we dig a little deeper?'

The gloved hand again touched Smith's scalp.

He and Serif were standing on a shale beach beside a cold sea at night, watching the beam of a lighthouse cycle round and round in the mist. 'This is the home that you fled?' Serif asked.

'Aberdeen, yes.' Smith took a deep breath of sea air and looked at his hand. It was whole again. 'Who are you? What do you want with me?'

'You don't know where the Pod is. I wonder if it has been destroyed. Laylock is sometimes very fallible, and on occasion... untrustworthy. If the Pod has failed, we may at least discover some important information about you. I know they have a lighthouse on a place called Gallifrey,' Serif murmured. 'Tell me, does Aberdeen have defences?'

'A sea wall, that's all. To stop the flooding. There's no soldiers here. Nothing special about the town at all, except for the rock - '

'Ah yes, the radioactive granite, so conducive to mutation.'

'No, the rock with "Greetings From Aberdeen" written through it. Very tasty.' Smith glanced up at the headland above the beach. 'Oh my God! Verity!'

Serif followed his gaze. A young woman with a moon-like, innocent face was staring down at them from the shore.

'Ah, so there is beauty in truth. Who is she?'

'A girl. We used to be together. Now we're not.'

'What does she mean to you?'

Page 15

'She's what I'm always just missing. We met here once. We were very different, from opposite sides of town.'

'Are some of the citizens of Aberdeen better off than others, then?'

'You could say that. There's a poor house, run by the Church. That's where I was brought up.'

'Really? What was the name of your teacher? What did he tell you of the sea wall?'

Smith opened his mouth, and suddenly found himself convulsing. He fell to the ground, his hands grasping frantically at the pebbles. It was as if something huge had given way inside him. 'No! No!' he shrieked. 'Can't tell!'

He reached out a hand piteously as the woman on the shore turned and walked away. 'Verity!'

'So you know there are certain things you should not say. Interesting.' Serif raised his gloved hand and clicked his fingers.

Smith found himself back on his own living-room floor again, paralysed. The pain flooded back into his finger. He struggled to breathe, and managed to gasp regular, shallow gulps of air as Serif got up and wandered over to his bureau. 'You've been writing fiction,' the dark man whispered, picking up a page from Smith's story and glancing at it. 'In fiction, we reveal our deepest unconscious thoughts. Would it be of any use to me to read this? You may speak.'

'Unconscious?' Smith gasped. 'How can thoughts not be conscious?'

Page 16

'Hah! What a primitive world this is you've found for yourself. Why, these humans must think of themselves so simply, as straightforward animals who think and do, decide and set about. Well, I know better, and so should you, as that deep-set defence mechanism I just uncovered indicates.' He squatted back down beside the prone teacher. 'My name is Serif. Unlike my fellows, I have specialized in matters of the mind as well as the body. I've often had cause to unpick the programming of a personality, rewrite certain aspects. I do this by regressing the subject right back to the moment of birth and then working forwards. In your case, of course, that's not really appropriate. However, we can make some progress. In doing so, we may learn all sorts of incidental things about dear, ripe Gallifrey along the way. Do you think that's how we should proceed?'

Smith snarled a response. A vast roaring of blood filled his ears and the pain from his finger was terrible, as if some healing machine was trying to start its work and failing. That failure was filling his senses with agony, and he couldn't decipher what on earth his assailant was saying.

'It was a rhetorical question,' Serif told him, and placed his hand back on Smith's head.

Smith stared at the woman whose head lay on his shoulder, her straight, backcombed hair warmly touching his skin.

They were both dressed in togas, lying on a lounger in the courtyard of a villa. The only sound was the gentle trickle of a fountain.

'There,' the woman said. 'That wasn't so bad, was it?' Smith was about to

reply, but then he was staggering back from a door, dropping his briefcase and

clutching his nose, shouting all manner of colourful swear-words.

Page 17

'It's one of these new automatic jobs,' a voice said. 'Still some teething troubles, what?'

But hadn't his brother told him about that? Funny how close to you some stories got, as if they were memories.

He was waltzing with a woman in a flowery dress, pleased at how her movements matched his. Around him men in uniform were all dancing with their partners. 'Perhaps we could go on somewhere?' he asked.

Under an orange sky, a group of dark figures stood around a singing structure, a million fine chords sighing in the wind. Information was flowing down the chords, being woven together in the mesh they were forming between them. Spirals of microscopic data had been flowing into the loom for days. Now something was due to emerge.

The woman walked forward and touched the chords. Something shaped itself into her arms. A male child.

'Again?' said the child.

'Again?' said Serif.

There was a crash, a thump and the orange sky became plaster-white again.

A woman was looking down at Smith, the remains of a heavy vase in her hands. Serif was lying on the carpet, his hand an inch from Smith's head, a surprised look on his unconscious face.

'Have you seen an owl?' Smith asked the woman.

'Yes,' said Joan. 'How did you know?'

Page 18

Smith was barely aware of Joan leaving again to run up the driveway to the school. She left Serif, who showed no sign of waking up, roughly bound by a sheet. She woke Mr Moffat the bursar up, and demanded to use the school telephone, shouting at the night operator that this was an emergency, a burglar had been caught and the police must be summoned.

A Black Maria stopped outside the cottage and Sergeant Abelard, an old man with a white Kitchener moustache, helped his two constables to lift the still unconscious Serif into the back of the van.

'An anarchist, by the look of him,' said the sergeant. 'One of these Russian fellows like as did Sidney Street. Perhaps it was him set off the poison gas in the hospital.'

'Poison gas?' exclaimed Joan.

'Sorry, madam, I didn't mean to alarm you. It's all dealt with now, the papers will be full of it tomorrow.'

'What happened?' asked Smith. He was wrapped in a rug, a cup of tea in his right hand, his left little finger bandaged up by Joan. She'd winced as he did as she'd bathed the end of it in alcohol.

'Somebody set off what we think must have been a gas bomb in St Catherine's.

We wired Whitehall and they said to have the fire brigade hose the place down.

They've been at it all day. Some of those lads got a look inside the place, and

what they describe... well, sir, I wouldn't like to repeat it in the company of

a lady. There's a convoy on the way from Clapperton. We'll hand the matter over

to the army boys when they arrive. Bit of a feather in my cap to have

apprehended somebody, though. What did he want here, do you think?'

Page 19

Smith stared at him. 'He must have been a burglar. He cut off my finger. Perhaps he was looking... for a ring? No, I don't wear a ring. He knocked me out. And there was something about an owl...'

The policeman flipped his notebook closed. 'I don't think he'll be much help to us tonight, madam. It's understandable. Could I ask you both to call at the police station tomorrow morning?'

Smith and Joan agreed, and thanked the police. The van drove away and Joan pulled up a chair to sit beside Smith, who was still staring vacantly into space.

'It is odd that you should mention an owl,' she said. 'I was about to go to bed, when I was disturbed by a great clattering at the window. I looked out, but only saw an owl flying away. I glanced down and there were your white gloves. You had left them behind on the sideboard. I had an odd fancy to return them to you. Nothing bold, I was merely going to post them through your letter box, with a note about seeing you tomorrow. When I got here, the door was open and you know the rest.'

'Do I?' Smith smiled gently. 'I'm very confused. I seem to have been dreaming, but I don't quite know where the dream ended and waking up began.' They talked for an hour or so more, and gradually Smith began to feel stronger, the fear of his attack draining from him and reality reasserting itself.

'Do you want me to stay?' Joan asked. 'I am capable of sleeping on a chair.'

Smith bit his lip and a slow grin chased the chill from his face. 'No,' he

decided finally. 'You get home to bed.'

Page 20

'All right,' said Joan. She got up and quickly kissed him. 'Bolt the door behind me.'

'Will I see you tomorrow?'

'That was the plan, but since you are now injured - '

'I can't think of a better cure than looking at you. What'll we do?'

'I shall make a picnic. We'll go along to the police station and then find some quiet spot to eat it, hopefully out of the range of poison gas.' She stopped on the way to the door. 'Oh my goodness, how will we know if our spot is safe?'

'Anywhere that birds still sing,' said Smith, 'one can have a picnic safely.'